The author shares findings from her action research, focusing on the question, “How can I use critique to improve the quality of student feedback, student work and create a culture of collaboration?”

As I watched my class interact close to the year’s end, I felt un-needed. This is a good thing. We had completed three extensive cycles of critique and revision in which students created websites, United Nation style documents, and maps. Students generated their own criteria for quality work by analyzing exemplary models (exemplar critique); they self assessed their work using those criteria; and they gave each other advice (peer critique). More than any other time in over a decade of teaching, I watched students take ownership of their work and be willing to make draft after draft to achieve high quality results. I also watched them willingly offer help to each other in pairs, groups, whole-class settings, and informally throughout the day. There were times of growth and times that felt like regression, but what I saw by the end was a much different group of students than I had at the beginning of the year. There was little to remind me of the first critique cycle, when so many students were afraid to speak to their partners.

By the end of the year, I saw students asking each other for ideas. I watched as a student showed his peer two versions of the same political cartoon and asked which one was better. Not only did that peer offer advice, but the other four people at his table chimed in, too. Earlier that same day I watched another student throw around ideas with his peers. In the first critique cycle of the year, Eddie, a genius at computer programming and many other things, did not talk to his partner at all. When I asked why, he said he did not need help. Later, in the second critique cycle, Eddie asked his friends, all of whom are also very high achieving and very insightful, over and over for advice. He collaborated regularly, but was selective with whom. He had little time for those students who struggled with the assignments, and showed little interest when asked to get advice from them or provide advice to them. Finally, in the third critique cycle, Eddie volunteered his help regularly to students of all levels, specializing in students who were struggling. He did not need to be asked by me or by the struggling students. He would see a frustrated student and offer his help.

Beyond this anecdotal progress, some clear themes emerged over the year for how to help students work together more, offer each other more solid advice, and take greater ownership of their final products.

Many teachers employ some form of what they call critique in their classrooms. Many have also run into the same problem over and over of how to get students to make simple changes and not leave their work half done. My research convinced me that in order for collaboration to grow and critique to be most effective in the classroom, it cannot be treated as simply an activity to be done on this or that day of the week. Rather one must approach critique and collaboration as issues of culture.

For collaboration to grow, students must be convinced of three things. First, they must believe that they truly are living resources for each other. This can be achieved through many activities that seemingly have little to do with critique. This was the point of early activities in my classroom: changing seating charts, sharing skill sets, looking at a first grader’s multiple drafts of a butterfly to show how peer feedback led to beautiful work. These activities did as much as anything to convince students that they could benefit from each other’s knowledge and feedback.

Second, collaboration must be so ingrained in the classroom culture that it is hardly recognized as such. Frequent practice helps students see critique, not as an activity, but rather as a necessary step in a process of creating work they are proud of. It is part of the product, not just something we do to make a product.

Lastly, students must learn to see mistakes as natural. This helps them take risks and understand that reworking is normal. Otherwise, the students can never be convinced that reworking their products will actually benefit them. Fail early and fail often, though it sounds crazy, is a great classroom mantra.

By bringing in models of exemplary work and having students critique them, I gained a more nuanced view of when the teacher should teach and when it is important to let the students teach each other. Lisa Soep’s (2008) work with peer critique led me to see the importance of students negotiating the standards by which their work would be judged. Ron Berger’s (2003) An Ethic of Excellence led me to have students critique exemplary models as a way for students to identify the standards to which they would aspire before they ever began the work themselves. However, my increased understanding in this area came primarily from my own experiences. The successes and failures I experienced when I provided, or did not provide, opportunities for students to identify criteria for excellence underlined that this step is one of the most important when conducting critiques.

For exemplar critiques, I found student models to work better than professional models. Students were more inclined to assume they could not achieve the level of quality present in a professional model. With student models, they could not use that excuse. Showing student models did not result in decreased student originality or cause students to “copy” others’ work, as is often feared. Rather it gave students the same knowledge I already had as a teacher: I had seen other work, and this had provided a framework for imagining even better work.

For exemplar critiques, I found student models to work better than professional models. Students were more inclined to assume they could not achieve the level of quality present in a professional model. With student models, they could not use that excuse. Showing student models did not result in decreased student originality or cause students to “copy” others’ work, as is often feared. Rather it gave students the same knowledge I already had as a teacher: I had seen other work, and this had provided a framework for imagining even better work.

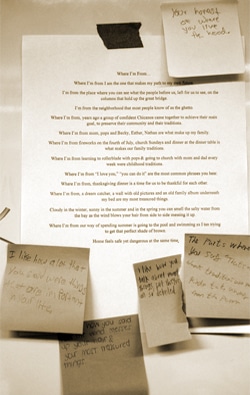

Whenever we did exemplar critiques I put three columns on the board. I labeled each column with a particular quality on which to focus when looking at the models. For example, when looking at model websites, before students created their own, I labeled the columns Layout, Design and Content Organization. These columns allowed me to designate what types of things were important without telling students what to do, and proved to be invaluable. Without such columns, students did not have enough direction to be successful, and each time I tried an exemplar critique without them, it failed. Exemplar critiques did not work when I simply asked students what they noticed or what struck them. Rather, I needed to ask them what they noticed about particular focus areas. Once students understood the foci, they could teach each other, and it became my responsibility to let them do so.

When students examined models and defined the criteria for quality work, they were able to identify and negotiate the core principles present in all good products. Collectively, they could then debate and decide when there were disagreements about what made for good work. As they debated, students dialogued about what was important until a consensus was reached, instead of just being told by the teacher. Nowhere was this more evident than in my very first exemplar critique of digital portfolios, when the picture of a gun-toting Angelina Jolie popped up. The transition from the comment, “That’s so cool,” to the consensus that it was cool, but not a professional or appropriate picture illustrated that though individually some students might make less than ideal choices, collectively they could make very strong decisions in their work.

Complex projects often require multiple exemplar critiques. For example, as we composed Model United Nations Resolutions, several smaller products led up to the final product. Each smaller product had a different purpose, and so each should have had a separate exemplar critique with different foci. At several points, in a rush, I did not do separate exemplar critiques for mini-products. Instead I gave the students teacher-generated rubrics. This was the point in the year when students struggled most with critique, felt more frustrated with their work, and I saw a decline in assignment completion. Generating their own standards really helped students to internalize them. If they did not go through this process, they often did not know where to go, even if the standards seemed clear to me as a teacher because I had told them what they were. The bottom line is that when students were set up for success through exemplar critiques, they felt more confident. They knew not only what they were trying to achieve, but how to comment on it in their own and others’ work. This in turn made them more invested, which led to more solid critique sessions.

Many of the teachers I have spoken to about critique see it mainly as a vehicle to improve work. While it is that, it is so much more. Although critique does result in stronger products, I do not believe that is the main justification for doing it. After all, there are much more efficient ways to produce solid work than hour upon hour of feedback sessions, in which you are never even guaranteed that the students will give quality feedback. Teacher feedback will more likely result in consistently high-quality feedback that students can safely and reliably use if they want to make a product better. It’s also much quicker, though not necessarily for the teacher.

Peer critique holds multiple benefits. When students look at their peers’ work to offer feedback, they have to think about what makes for quality work. When students receive feedback, they have to think about whether the feedback their peers gave them is good feedback or not, and if they will use it or not. Lastly, when they have the opportunity to look at so many of their peers’ works in progress, they begin to see learning as a process itself, transforming what they once saw as isolated activities into communal endeavors. Students inevitably get to see how others solve similar problems and gain a broader knowledge and experience base to draw upon when encountering difficulties and creating quality work of their own.

In contrast, when teachers provide feedback, students are more likely to blindly take the advice. While the end product might be higher quality, it will not necessarily be more perfect. It is important that we remember that the perfect product should be a reflection of the student’s thinking process, not just a fine product in itself. If the fine product comes from my advice, blindly taken by a student without thinking, then the product no longer becomes a reflection of the student’s thoughts, but of my own thoughts executed by the student.

When students accepted the value of reworking their products, their work showed considerable improvement. While the students’ realization of the importance of drafts started early in the year when looking at six drafts of butterfly drawings made by a first grader, the actual acceptance of how important drafts were grew as the year progressed.

When students accepted the value of reworking their products, their work showed considerable improvement. While the students’ realization of the importance of drafts started early in the year when looking at six drafts of butterfly drawings made by a first grader, the actual acceptance of how important drafts were grew as the year progressed.

After reading about a study in which students who were told they must have worked hard took greater academic risks and attempted more difficult work than their peers who were told they were smart (Lehrer, 2009), I thought about how students often perceive drafts as something you do when you don’t get it right the first time. This moved me to talk often with the students about the value and inevitability of mistakes.

Engaging in various activities between drafts helped emphasize the usefulness of reworking. Models helped students realize what was possible and to set goals for what they wanted to achieve. Student-generated criteria provided a map to get there. Self-reflections and peer critiques gave students opportunities to look back at the student-generated criteria and remind themselves where they were headed. All of these activities combined helped even the most fearful students. Sitting and not talking in activities did not always signal disengagement. For students who felt unsure about what made for a quality product, and even less sure about speaking in front of their peers, quietly watching and listening to each of their peers’ draft critiques provided another chance to figure out how to complete an assignment.

Shifting from a teacher-centered to a student-centered model was instrumental in getting kids to do more reworking. Without this shift, students would still be completing drafts, but just because I told them to. It seems to me from my years of teaching that drafts that are completed “just because I had to” usually have minimal changes. Rarely do you see the type of reworking that was present in most of my students’ work. You also do not see the begging to do more and more drafts, like groups often did by the end of the year in my classroom.

One of the beautiful things about teaching is that it is a marathon, not a sprint. While it is difficult sometimes as teachers to cede control of our classrooms, especially to a mob of youth, it is comforting that when an activity does not work there is always the next day in which we can try something new again. I believe undoubtedly that it benefits students when teachers allow them to exercise more control in the classroom. While this may seem foreign to the traditional structure of schooling and classrooms, it has many forms and innumerable benefits.

Students can assume more control in the classroom in many ways. They can define criteria for quality work instead of teachers handing out pre-made, teacher-generated rubrics. They can advise peers about how to achieve quality work instead of teachers spending endless hours writing notes on papers. Students can facilitate critique sessions instead of teachers always keeping order. They can also advise teachers how to fix critique sessions when they seem broken. With solid protocols, students can help police each other to ensure that critique sessions remain effective. Through all of these methods, students gain ownership over the process of the work. They begin to see their work more as something they do and less as something that a teacher makes them do. As a result, they often rise to the occasion and take on the challenge of creating higher quality work.

By far the most important things I learned about critique and collaboration came from my students. Sandra summed up the value of the experience best, in far fewer words than I ever could, when she said, “When I collaborate with others, I can see an improvement in my work, and that helps me strive to work harder.”

To learn more about Juli Ruff’s work with critique, visit her digital portfolio at //gse.hightechhigh.org/digitalPortfolios.php or purchase her book, Peer Collaboration & Critique: Using Student Voices to Improve Student Work at https://www.hightechhigh.org/projects

Berger, R. (2003). An Ethic of Excellence: Building a Culture of Craftsmanship with Students. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Lehrer, J. (2009). How we decide. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Soep. E. (2008). Learning as Production, Critique as Assessment. UnBoxed, 2, Fall 2008.

Tags: