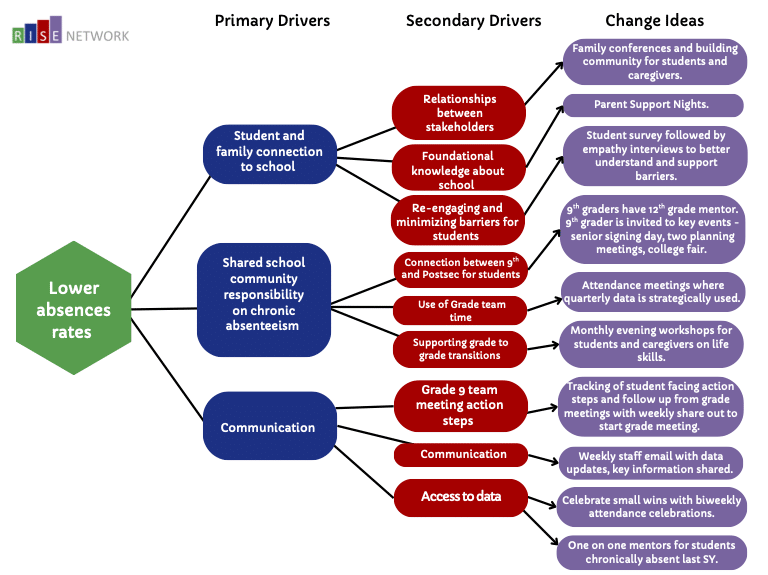

A Picture of a Driver Diagram:

Linzi Golding:

Even when it’s small change, it’s still change. So creating spaces to celebrate that and to find the wins, no matter how small they might be, is something that I would’ve told myself when we first started out on this journey.

Alec Patton:

This is High Tech High Unboxed. I’m Alec Patton and that was the voice of Linzi Golding, a school improvement specialist at the Connecticut RISE Network. RISE has been around since 2015. They facilitate statewide networks of public high schools across Connecticut, helping them use data to learn and improve together. In the spring of 2024, some of Connecticut RISE’s partner schools started explicitly focusing their improvement work on tackling chronic absenteeism.

This episode came about because I had a conversation with Linzi and two of her colleagues at RISE, Engagement Specialist Erin Asselin and Senior Evaluation and Data Analytics Specialist Melanie Gonzalez. And I was struck by how much they’d already learned from this not quite one-year-old chronic absenteeism project. So after that first conversation, we got together and talked about it again, this time with the recorder going. In this conversation, we talk about keeping things simple, about celebrating small changes, about smart ways to share data with schools, and about how to recognize and celebrate effort, even when it doesn’t lead to the outcomes we were hoping for.

And we start by talking about driver diagrams, so I need to take a moment right here to tell you what a driver diagram is. I’m going to give you Dr. Brandi Hinnant-Crawford’s definition from Improvement Science in Education: A Primer, because that’s the book I go to whenever I get confused about specialist improvement language. Here’s Dr. Hinnant-Crawford’s definition. A driver diagram is a tool that illustrates your theory of improvement. It contains your desired outcomes, key parts of the system that influence your desired outcomes, and possible changes that will lead to desirable results. Dr. Hinnant-Crawford adds that a driver diagram looks like an organizational chart turned on its side. If you’re having trouble picturing that, we’ve got a link to a picture of a driver diagram in the show notes.

With that, here’s my conversation with Linzi Golding, Erin Asselin, and Melanie Gonzalez. We’ll start with Erin explaining why she’s become such a fan of driver diagrams.

Erin Asselin:

The driver diagram just really helped illustrate for me that when I did this last year, the previous school year, the change ideas were too broad. They were too big and they were so lofty. The school I alluded to before that had some gains so far this year, their change idea last year was that 88% of their students are going to be on track, it would be an 11% gain from the prior year. But that’s all it was, that was their whole change idea.

And at the time, I was like, “Okay, great. That’ll be your change idea. You’re going to change you’re on-track rate.” I’ve now come to realize, because I read that chapter, that that is not a change idea whatsoever. I think it’s probably more in the category of an aim statement, as I think about the driver diagrams, and it’s like they’re working towards that goal and that goal is great. The school they were at, yes, we want more students to be on track than 88%, but for them that was a huge gain. But at the end of that year, they actually only had 72% on track and so they fell really, really short because they change idea, which wasn’t a change idea, was way too broad, it was way too big and they couldn’t make traction on it.

This year, they are far more specific. We got really into the weeds and the data and we found that a small change idea, they are going to move 34 students. We found these 34 students because we went real deep in the data and we said, “Okay, who are the students coming to school sort of, some of the times?” We picked about 80% ADA, average daily attendance, kids who are showing up, they have some routine of coming to school, but it is not great. They’re not showing up all of the time. And if they keep that up, they’re going to hover around chronically absent. And we said, “Let’s focus on them. Let’s build some habits, let’s get them invested in school. Let’s talk to them, let’s find out what’s going on.”

And they are slowly, over time, building stronger habits, building a stronger connection, and getting those kids back into class, building more habits to be more successful to want to be in school. And so far they’ve gotten 15. I was just checking the data today, they’ve got 15 students that are on track. A few more are going to trickle in because midterms are slowly populating. So I’m hopeful by the time semester one grades fully lock, they will have a few more in. But by focusing in and making it small and meaningful, anchored in data, we’ve been able to see more substantial change.

So I’m hopeful that when they, they’re going to add some more on Friday at our collaborative, they’re going to be able to pick a few more students to add to this list, probably to bring it back up to around 30, so they can continue that push as they go into the next semester. They know for that other 15 that they weren’t able to move, what they need to do. It’s bigger attendance issues, it’s transportation, it’s safety in the neighborhood, and it’s algebra. Some students just need more support in algebra. So they have things in place, whether it’s tutoring, after school support, things of that nature to really build those skills up so that students hopefully can be more successful by the end of the year. But it’s really about those little things.

Alec Patton:

Yeah, two things that brings up for me is one is just that I can just see that that first, that 88%, that was like the entire school population is like how you’re going to be looking at that. And the difference between that and, “Hey, these 34 kids,” is really powerful.

And I think the really amazing thing then is that when you’re looking at 34 kids and you get, as you’re going to get, variation within that 34, then you end up with being like, “Okay, we got these 15,” and it’s so much easier to, for me just hearing it, to get my head around. And I think that’s awesome.

Erin Asselin:

That small group they have left, they know the story of every single one. When I meet with the AP, he just lists off exactly what’s happening with those kids because they know exactly what the story is. They know exactly what they’re working on, what they need to do to support it. It’s just a longer story.

Alec Patton:

Yeah. And I think the other really powerful thing is that what you’re learning from those 17 kids, that school and all the other schools in the network are going to be able to apply to other kids who are in similar situations because those situations are going to come back up again.

Erin Asselin:

Absolutely.

Alec Patton:

So it’s actually like paradoxically, it’s much easier to scale if you go down to that human level than it is if you start big and try to stay big.

Erin Asselin:

Absolutely.

Alec Patton:

I’ve got another piece of advice you told us about, that I’m hoping you’ll unpack. Here’s what it is. Change ideas don’t need to be as complicated as I thought they needed to be.

Erin Asselin:

I think that goes back to what I was saying earlier as well, just that I thought they had to be big and grand and just very complicated, a lot of moving pieces. And I’m realizing that the simpler, the better.

Alec Patton:

What taught you that?

Erin Asselin:

I think the example I just gave. It’s that the more complicated they are, then the more they fall apart. The busyness of the school, the things that pop up throughout the school year that pull you off track, when they are simple and target specific data points, then you can celebrate success. Then you can see when things are breaking down and you can create a plan to be like, “Okay, this isn’t working. Here’s how we’re going to figure out how to tackle it.” When it doesn’t have so many moving pieces, then you can support when you need to tweak and change.

And I think going back to that chapter, the chapter 10, it’s really about the change ideas aren’t super complicated because you might have a couple of them. And as one works, then you really kind of lean into that. And when you find that something really isn’t working, it kind of falls away. So that idea of as something works and you start to gain traction with it, you’re really leaning into it and you’re tweaking it and you’re changing it to fit the context of the school, the needs of your students. And that’s where the nuance comes in.

But the idea itself doesn’t have to be this overly elaborate, this super complicated thing. It’s about what is the nuanced idea, the something we haven’t tried, the being innovative and creative to really support kids.

Melanie Gonzalez:

Yeah, I just wanted to respond to what Erin said because I think it’s something that we see in data a lot or in program development and implementation where we create this ambitious goal that we want to achieve and we want to accomplish it right away and we don’t want to experience any mistakes or setbacks. And that’s really unrealistic, right? Any program that thinks is perfect is not and is really experiencing some blind spots. There’s always going to be challenges to a program, whether it’s its design, its implementation, resources, whatever it may be.

So I say that to say that part of the beauty of implementing change ideas is learning from them, really making sure that these are learning opportunities and opportunities for us to be real with ourselves. We may think something is going to be a great change idea based on the experience that we have in school and then we implement it and we don’t see any change in the data.

And I think you have to have an open and growth-like mindset in this work in order to really honor the students that you’re serving, the schools and communities that you’re serving. And understanding that you’re not always going to be right, but let’s try new things and let’s see if they’re working. And if they’re not, let’s pivot and try something new.

So it doesn’t have to be complicated, but I think it has to be honest and I think it needs to… You have to be humble in a certain respect and open to that learning that comes with change idea implementation.

Alec Patton:

And Linzi, did you want to jump in?

Linzi Golding:

I did. So to piggyback off what Erin shared and also what Mel shared, advice around what we would tell ourselves back in 2023 and the spring of 2024 to now really is that even when it’s small change, it’s still change. So creating spaces to celebrate that and to find the wins, no matter how small they might be, is something that I would’ve told myself when we first started out on this journey. And we heard Erin talk about our approach in the beginning was this is the end goal, we need to get here, here, and here. And when things started to fall flat or efforts were not leading to making it seem like our school partners were going to achieve those things, the pivot and the strategic shift towards thinking about, oh, this is still our change idea, but in order to get there, let’s take these baby steps and celebrate when we win on those, in order to really get to the bigger picture, was not always in place. And it is in place with a lot more strength now.

So really just wishing that I knew then what I know now about small incremental changes are still changes and folks are still working at doing something. So that has merit and is valued and seen and should be celebrated on a regular basis.

Alec Patton:

Awesome. And what should folks know about the Data Hub?

Linzi Golding:

The RISE Data Hub is a secure and action-oriented data platform that’s built by educators and for educators, which promotes on-track achievement and post-secondary success for all students. Our Data Hub just streamlines many data sources into one, what we like to believe it is, is user-friendly interface. And it supports teachers and counselors and administrators in an effort really to efficiently and effectively support all students.

Alec Patton:

Thank you. Mel, can you say more about how you think about visualizing data in ways that helps to identify and celebrate those small wins?

Melanie Gonzalez:

Yeah. A lot of schools within our networks, they face a lot of challenges that make the achievement of on-track success challenging or efforts to reduce chronic absenteeism challenging. There may be schools that have high levels of chronic absenteeism and they could even be concentrated in specific districts.

So sometimes when we visualize this data based on where they’re at, it can create a sense of helplessness or a sense of like, “Oh, we’re not doing as good as the other schools in the network.” Or on the flip side, “Oh, look at where we’re at compared to the other schools, we’re doing so wonderfully.” So when you’re looking at those overall outcome measures, it creates this feeling of who’s doing better than the other just in that achievement sense. But there’s lots of contextual factors that play into those outcomes that are not dependent on all the hard work that these educators are doing, such as policies or student factors, transportation, whatever it may be, community factors that are resulting in the data appearing as they do.

So typically, historically, RISE, we have, when we present data, it’s usually like, okay, what are your on-track rates? What are your chronic absenteeism rates? And people see them in that way. To support what our change idea work, we’ve started pivoting towards reporting on the changes. And something interesting about that that I’ve noticed, just from this past analysis of data for some convenings that we’re going to have coming up and we’re going to be sharing some data on quarter one to quarter two changes in chronic absenteeism rates, is that some of the schools that are high performing have those low levels of chronic absenteeism. They may also have the lowest levels of change. So it’s a way for people to see the data in a different way that is really focusing on the change instead of the overall outcomes, which I think is going to be interesting to see how they respond to, because it may change the ways that people view their districts. Sometimes when schools are doing well, it’s like, “Oh, we’re doing good.” It may create less motivation to actually implement change ideas that are going to improve their outcomes.

So anyways, we’re just playing around with this new way of sharing data stories and I’m really interesting in thinking about how it’s going to motivate the educators that we work with and also assess the impact of our change ideas moving forward. Right? Because those schools where we’re seeing a lot of positive changes, even if they’re some of the schools that have the overall lowest outcome rates, we can learn from them and we can highlight them as bright spots, which is going to be really exciting. And I don’t know, Erin or Linzi, if you have anything else to add to that from the network perspective?

Linzi Golding:

I can chime in here. And Mel really did a beautiful job of just summing up what we’re learning. And we’re really focusing on trying to focus on the changes that are occurring in our outcomes rather than putting all of our eggs in the outcomes themselves. So using our Data Hub and our data infrastructure that we have here at RISE really lends itself to being that system that collects and tracks and reports out on data.

We are stepping away from worrying about getting to our goal in like one leap, our change idea in one leap. And instead, we’re using looking into change through variation and using all of the data that we are collecting and that we’re analyzing to backwards plan in smaller ways and chunking out our goals in those incremental ways so that we can have more wins that put us on the right track to eventually achieve or get close to the goals that we have set through with our partners, through our change ideas.

And that doesn’t mean that we’re not worrying about that. We’re still worrying about whether or not we’re there, we’re on the right track, but we’re not worrying that this one change idea is perfect and it covers everything, and that this one idea is going to cover the thing to get us there. We’re taking pause in the process and really thinking about what can we do for this period of time that’s going to get us to move forward.

Alec Patton:

The final thing I want to talk about is something that I think can feel kind of uncomfortable in this work, that you talked about, which is effort versus outcome. Because a point that I’ve heard from you is that this work is hard, which we know, and it involves trying a lot of stuff that might not lead to positive results by definition. And I think continuous improvement teaches us to be pretty ruthless about that. If it’s not working, change it up. And on a podcast, that sounds great, but in real life, that change idea that didn’t work or didn’t lead to a shift in the data, it probably took a lot of effort. Because we talk about low effort, high impact, but low effort’s a relative term and even stuff that’s low effort in a school probably takes a lot of effort because you’re doing so much. So I’m interested in how you’re thinking about celebrating effort that doesn’t lead to a shift in data.

Erin Asselin:

I think the effort that goes into it is huge. And even when the data doesn’t show the change we were hoping for, I think we still learn a lot from that.

We are actually doing this exact effort to impact a kind of matrix at my collaborative in two days. And one thing that I’m hoping my team is able to walk away from and think really strategically about is kind of the why behind it. So we put our effort and they do, all the teams I work with are incredible. They’re incredible, they are hard-working, some of the smartest people, as all educators are. I think there’s something that we missed, and so trying to figure out what is it? What was that reason it fell flat? We put this effort in, we had the best of intentions, but for some reason something didn’t click.

So as much as we wanted it to work, we still can learn. And that’s the kind of messy part of the change idea that we are truly trying to embrace. And I think we ourselves have kind of gone through that as well. In my example from before, it didn’t go perfect last year. And instead of being like, “Oh, I have to throw that out, start again.” No, I’m trying to embrace the messy, learn from what didn’t work.

I put a ton of effort into the coaching, into all the different aspects, just like all the educators I work with do. So really trying to think about, okay, where did I find success? How can I celebrate that? Where do I need to make changes? Who can I go and learn from? How can I collaborate with other people?

And I think it’s that idea of how can we, in our four hours that we have, really harness the collaborative spirit of the room, learn from each other, hear what worked, but also hear what didn’t and try to put our heads together and say like, “Ooh, maybe try this. Maybe this is what’s missing. Did you do that? Here, this worked at my school.” But really be able to come together and think about that so that that way the next time, the tweak we make, the change will be better, so they don’t go through that same process again.

Linzi Golding:

Around effort, there’s this very special balance of finding how to keep motivation high when lots of effort has been pouring into something that’s just not moving forward. And those spaces that we heard Erin talking about are super pivotal in our network to bounce ideas off of, to iterate on, “Hey, what are you thinking about this?” From a role-like perspective and then from a broader lens of folks in different roles across our schools.

As well as mindset work, right? So whenever we talk about effort, there is, you can’t talk about that with without really thinking about what are the mindsets and what’s the workaround mindsets that we want to win at, that we want to continue to develop? And it’s this idea of not yet. So really being intentional with the professional development that we’ve been offering is, although we may not be seeing the changes that we had anticipated yet, what can we do now to make even just the smallest move forward? Maybe and it’s a difference in our practice, maybe it’s a difference in our mindset, it’s a difference with the folks on the team. What’s in our locus of control when we keep our effort high? And really trying to shy away from the abandonment of ideas until we’ve exhausted every literal avenue, ourselves and our community partners and other folks who are doing just similar work.

So it is definitely a balance to find ways to keep that motivation high in our school partners and those closest to the work. But it has really, really awesome rewards when we can shift our mindsets towards that.

Melanie Gonzalez:

And I think one of the struggles that folks have is that they’re so scared of failure. But I know there’s some research articles out there that some of the most cited research are research on failure, on things that we’ve learned from that failure.

And I think at RISE, we’ve been working a lot on thinking about our strategies or ideas or the ways in which we do our work. Historically, I think we’ve thought about it a lot using the little T theory, so theory about root causes or why things are as they are in schools, because of our personal experiences and things that we’ve observed in the schools. And recently, we’ve been starting to expand that approach to include big T theory, so theory from best practices and research in the field.

And I think both of those types of theories are very important. And I just think that all the learning that folks get from both their failures and their successes can help us in really creating strong theoretical frameworks and understandings of our work, utilizing both those big and little T theories. Again, that’s why I think being honest is so important, being humble in this work because failure is a part of it. And just because one fails doesn’t mean it has to be a negative thing, especially if somebody uses it as a learning opportunity.

Alec Patton:

Is there anything else that any of you want to add before we wrap up?

Erin Asselin:

Can we mention our grade nine symposium?

Alec Patton:

Tell us about it.

Erin Asselin:

So we hold a ninth grade focus conference every year. This will be our fourth straight year. And it’s just a really great learning venue to learn really a bunch more about the crucial middle to high school transition in a community of educators. It’ll happen in June, and we’d be excited to have anybody join us.

Alec Patton:

All right. Linzi, Mel, Erin, thank you all so much. This has been a delight. It’s been illuminating. I’ve learned a lot, thank you so much.

Linzi Golding:

Thank you, Alec.

Erin Asselin:

Thanks, Alec.

Melanie Gonzalez:

Thank you.

Linzi Golding:

Bye.

Alec Patton:

Bye.

High Tech High Unboxed is hosted and edited by me, Alec Patton. Our theme music is by Brother Herschel. Huge thanks to Linzi Golding, Erin Asselin, and Melanie Gonzalez for this conversation. We’ve got information about Connecticut RISE in the show notes, so check that out. Thanks for listening.

TAGS: