Imagine peering down an ordinary school hallway, clutching an entry ticket that was sent to you. You turn a corner and stop in front of a wall. There, you spot a concealed opening and step through to Diagon Alley, the hidden magical market from JK Rowling’s Harry Potter novels. All types of wizards are buzzing around the street. A few are checking tickets and welcoming parents, teachers, and a few journalists. Others are selling magic elixirs, cookie frogs, jelly beans, and lollipops disguised as brooms. Selling these items is an excellent way to start a conversation with the guests, and this is important—in fact, it’s the whole point of the exhibition.

In real life, the “wizards”—who range in age from 5 to 17—are students in an intensive Danish language program and come from a host of countries, including China, Congo, France, Germany, Kenya, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Thailand, and Ukraine. They can spend up to three years in this program learning Danish before joining “regular” Danish classes. If you look around Diagon Alley you’ll also see me, in a cloak helping the students navigate sales, and supporting their language as needed.

This exhibition is the culmination of The Harry Potter Project, an eight-week unit I designed and led with my teaching team in November and December of 2024 at Vestre Skole (School) in Billund, Denmark. Helping my students run immersive theater events was not the sort of work I took on early in my career, to put it mildly. But four years ago, the municipality of Billund decided that all schools should adopt project-based learning techniques,1 and it was the best thing to ever happen to my teaching career. I have changed from being a teacher who focused mostly on delivering information to my students to one who develops their hard and soft skills through innovative projects like this one. I have gone from seeing myself as a lecturer who provides worksheets to a facilitator who collaborates with my students and colleagues.

The Harry Potter Project took its first steps in June 2023, when we asked our students what they would want to work on the following school year. In order to do this, we followed a process adapted from the University of Reykjavik:

Each student is given 10 minutes to write on post-it notes all the things they would like to work on the following school year.

Students divide into groups of four, where they share their post-its and organize them under common headings.

A member of each group writes their headings on the board. Then each student votes for their favorites by putting a dot next to it (each student has two votes). After each round we eliminate the headings with the least votes, and keep going until we have five headings left.

The teachers take the five headings and work them into the projects they will create in the coming school year.

Using this process, students settled on the following five ideas:

The teaching team decided to begin the year with a Harry Potter project focusing on the first book in the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.2 We chose this because our students were aged 5–17 and it is the most accessible book in the series—also, most students were already familiar with the story. We decided early on that we would design a single project for all students and adapt the topic to different ages. We communicated our idea to students’ parents, and for the younger ones, we got their parents’ consent to read the book.

Once we had our topic, we came up with products for students to make—for example, boxes for chocolate frogs and all types of brooms. However, we struggled to come up with an exhibition concept that would showcase our work as a collective, rather than just as individuals. I came up with the idea to create our own Diagon Alley as I was reading the book for the tenth time and once again found myself immersed in the description of the street. Our school has these long empty hallways that are perfect for it. Also, students had already built booths for a street food project the previous year, and I thought they could repurpose them as magical market stalls.

Three weeks before the project began, all students received an acceptance letter to “Vestre School of Magic.” They were asked to bring to class three pencils, one eraser, one protractor, one pen, one pencil sharpener, one backpack, one pencil case, one mason jar, and their Quidditch clothes (that is, a change of clothes for PE).

The students were promptly guided to our movie room, where we watched Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Once the movie ended it was time for the sorting process. All students took an online placement test to determine which Hogwarts house they belonged to, and met the teacher in charge of their house.

Each school day was divided into two parts. In the morning we focused on reading the story, learning math concepts, writing, and exploring the fantasy genre. In the afternoon, we focused on making products. Students could choose what to make from a menu of products designed to suit their range of ages. Once a student chose a product, they had to commit to completing it.

What does group work look like when you have 50 students who speak 11 different languages? There is a lot of fun, frustration, laughter, and pride—as well as careful scaffolding from the teachers.

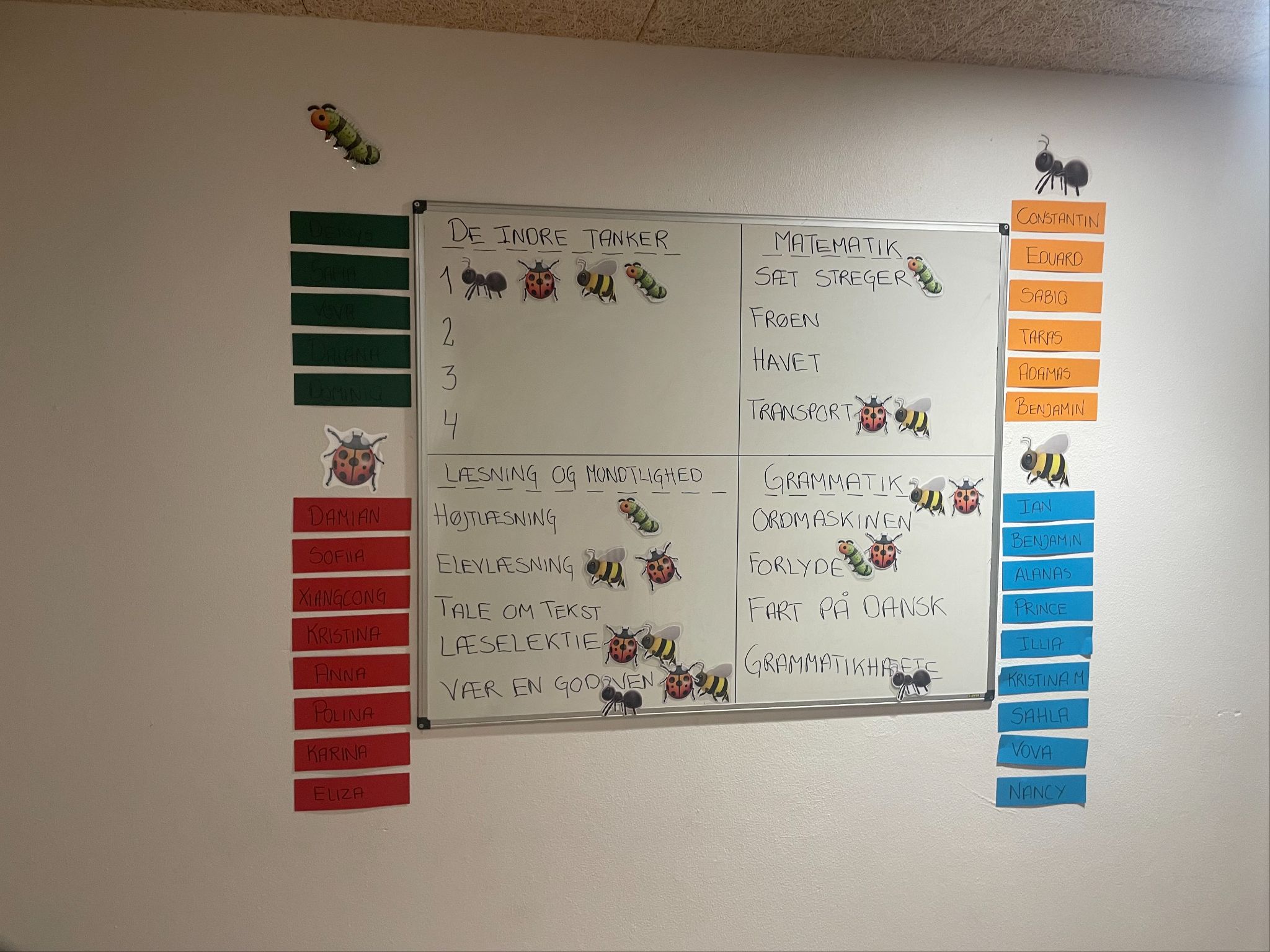

First, we split them into groups that consisted of students who spoke multiple languages—this gave them more opportunities to practice their Danish. To ensure everyone knew what they were working on each day, we used scrum boards (see Photo 1). Scrum boards are tremendously helpful to projects because they allow students to choose their task and require them to explicitly decide what they will be doing. It’s also easy to check the board to see what any student should be doing.

Photo: Scrum Board

At the end of each day, we checked in to see if students had completed the tasks on their scrum board. We also discussed where they had worked well together and where there was room for improvement. We then looked at their products to assess the quality. At this point, we took a cue from Hogwarts and awarded (and sometimes took away) “house points.”

Teacher collaboration is demanding—especially in a project as complex and all-encompassing as this one. I’d like to say it was all smooth sailing for our teacher group in those eight weeks, but it was not. We had to work hard to communicate well and provide detailed information when one teacher handed over responsibility for one aspect of the project to another. We spent a lot of time improving this process, sharing documents in Microsoft Teams and having weekly team meetings where we focused on the week ahead.

Each teacher was assigned a specific area in which to work. I focused on writing, grammar, and vocabulary. My colleague Helle worked on reading, Lene worked on movie analysis, and Leif focused on math.

The product-creation process was more fluid, because we had more groups working at the same time than we had teachers. To create consistency, we made sure each teacher was responsible for signing off on a specific category of finished products.

We made all the smaller products during the first seven weeks of the project. Then in the final week and a half, we built the large elements that would bring Diagon Alley to life, beginning with painting paper to cover the walls with scenes that provided a stunning background to the exhibition. Next, students assembled and decorated the booths. On the day before the exhibition, we put everything together and finished the last details. At this point, students were also developing and rehearsing their presentations. To make sure they were ready without making everything seem over-rehearsed, we asked students to write an account of their process throughout the project and specify what they did with each other.

Diagon Alley was bustling. Parents from other grades couldn’t help but stop by, drawn in by the sounds of chatter and mystery. Students explained the sorting hat they created, and spectators enjoyed trying it on. At one booth, two boys used all their salesmen skills to make sure everyone bought at least one chocolate frog. At the broom stand, an older gentleman and a student conversed in Danish, intensely and passionately. This was especially satisfying to see, considering that the student had only lived in Denmark for six months.

All over, students were engaging with their visitors—sometimes with assistance from teachers, but mostly on their own. It all felt, not to put too fine a point on it, magical.

In the week following the exhibition, the teachers reflected on the project. In retrospect, we realized we did not explain its full scope thoroughly enough at the start, and students had a hard time seeing the big picture. However, despite this confusion (and perhaps because of it), the students were able to contribute their own ideas to the project, many of which improved on our initial concepts. It was fun to learn about Harry Potter and the topic certainly kept students’ attention, but what was most important was developing their ability to communicate with native Danish speakers who didn’t already know them.

When we spoke to students about the project, what came up most often was their interest in Harry Potter. About two-thirds were already familiar with Harry Potter and Hogwarts, but even those who discovered it during our project loved working in this magical world. Students also told us they liked the way the day was divided into academic mornings and creative/maker afternoons. One concern that came up was that it was hard in the beginning, because they couldn’t imagine the final product. But once they understood that, they found it easy. This also meant that students worked really hard and occupied themselves with the details, wanting the products to be close to perfect. It turns out that when you combine a compelling topic, an authentic audience, and robust project management, the results are magical!

See below for a list of the skills we wanted students to develop in this project and the products that showcased their learning.

Literacy

Math

Soft Skills

Products

1. In Billund we use actually use the English phrase “Playful Learning,” not “Project-based Learning”

2. Published as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone in the United States

Tags: