“Tik Tik One, Tik Tik Two.” The room reverberated with the sound of 30 children shouting in unison, but Aasiya was oblivious to the noise. Eyes gazing into the distance, a look of deep concentration on her face, her hand scrabbled inside a large brass pot, feeling each item hidden within, trying to guess if it was the prize she wanted. She had waited a long time for this moment, patiently reading a storybook in a language unfamiliar to her family. And this was the payoff! A prize from Mr. Reading Pot himself!

That reading is foundational to learning is an uncontested fact. Research demonstrates that reading aids language acquisition as readers subconsciously pick up grammatical structures, spellings, and vocabulary (Cullinan, 2000; Jouhar & Rupley, 2021; Mackenzie, 2025). Reading stimulates the imagination, as children are drawn into magical worlds, far from their own lived experience (Sumara, 2002). Reading also aids socioemotional development by fostering a sense of empathy, curiosity, and perspective taking (Parry & Taylor, 2018). More importantly, reading with guidance and scaffolding from teachers and parents builds deep understanding and higher order thinking skills (Pearson et al., 2020; Sanden, 2012).

When my husband and I started my tiny, progressive academy, Al Qamar, in Chennai, India in 2009 (read more about it here), we were determined that our school would be a reading school. Naively, we believed that simply providing access to books would be sufficient to instill a love of reading in our students. Each classroom had its own library stacked with well-loved books, often from our personal collection. Unlike most school libraries, our students were allowed to borrow as many books as they liked. Unfortunately, I soon realized that the students were not even touching the books, let alone borrowing them.

Hmm! I wondered if children felt that the books were to be seen, not read. I asked the teachers to start displaying some at the end of each day so students might remember to take them. No go. A few kids borrowed books. The rest simply went home. Bookless.

I soon realized the magnitude of the problem. Books were not commonly found in these children’s homes, where families typically watched TV for entertainment. Adding to our challenge was the fact that our books were in English, while Urdu or Tamil were the languages spoken in our students’ homes.

To address these issues, we organized regular workshops for parents on the advantages of reading in any language. Over time these workshops helped convince parents that reading was the intellectual version of a superfood—loaded with goodness. We noticed that more books were being borrowed. To our disappointment, we also noticed that the books were being returned unread. When we asked students basic questions about the book, their blank looks or confusion told us what we needed to know.

We realized it was not enough to convince parents that reading was important. Parents had no idea what to do with the books, and were underestimating how difficult it is to read with a TV blaring in the background. They didn’t know that reading aloud to kids has a multitude of benefits and fosters many skills (Beck & McKeown, 2001; Duursma et al., 2008). Parents also struggled to have a discussion about a book that didn’t end up as a moral lecture. They had fallen into the same trap as we had—they believed that simply handing a kid a book would make them want to read it. We modified our workshops to focus on tips and techniques for building a culture of reading at home.

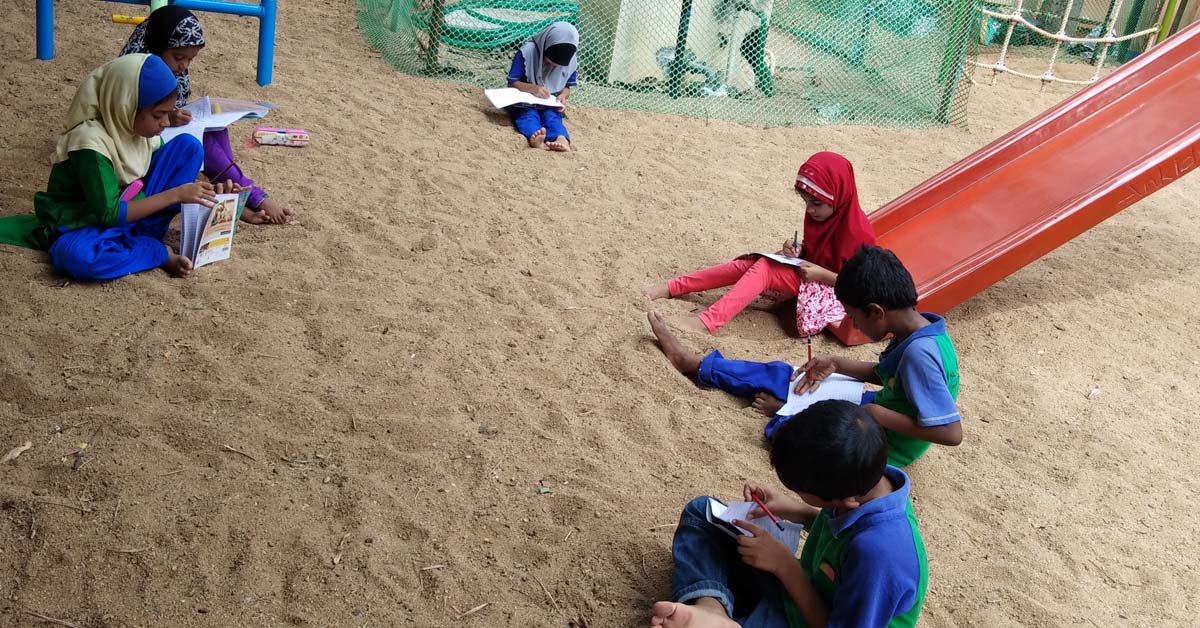

We made some progress, but not enough. I realized that we were expecting the magic to happen at home without creating the culture at school. So now, in addition to having libraries in the classroom, we needed to make sure students not only had access to books, but actually wanted to read them. In the younger classes, we started doing daily read-alouds, so students would see reading as something that is both exciting and part of a regular routine. For the older ones, we launched DEAR time. I had come across this concept while trawling websites for reading ideas. DEAR stands for “Drop Everything And Read.” We blocked out the last hour of school for DEAR time, for all classes. Realizing the importance of adult role-modeling, I requested the teachers to also drop everything and read—two birds with one stone. The teachers, who themselves had not been readers, got introduced to the wonder of books. DEAR time was fun. Kids were found on the playground, reading. Under the mango tree, reading. Nestled in a beanbag, reading. Even burrowed under their desks, reading.

Now that we had introduced kids to the magic of reading, I started hearing unusual complaints from middle school teachers and parents. “He’s reading all the time.” “She’s not completing her chores at home because she’s reading.” “I found her reading in a corner…during class!” I took these complaints as a positive indication that the tide was turning—the bookworms were emerging.

Naturally, once students started reading enthusiastically, they next began discussing their books. I would overhear conversations at lunch, near the lockers, whispers in classrooms, about the latest book they had finished, and one their friend should read too! A brisk trade started up as students swapped books. Even the most reluctant readers started getting pulled into the discussions. To keep up with the “in” group, they had to drop their inhibitions about reading and just dive into a book.

This was the scene at our tiny middle school, with only 15–20 students. However, our elementary school was much larger, with over 50 students, and culture change takes time. Kids were reading—both at home and during DEAR time—but because they were told to. As a result, they were not challenging themselves or progressing to more complex books. We tried getting them to write book reviews, but their response was lukewarm at best. As an older kid put it, book reviews destroyed the enjoyment of reading.

We were at our wit’s end.

Then I read about Read-a-Thons, book reading marathons where kids read as many books as they can in a given period of time. We brainstormed how to adopt this program at Al Qamar. Around the same time, I was reading Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The Golden Ticket! Yes—that was it. We needed a very attractive prize at the end of the Read-a-Thon to incentivize kids to read. Pedagogical wisdom also kicked in. I knew that young children need instant—or at least reasonably swift—gratification. They were not going to wait until the end of the term to win a Golden Ticket. They needed some little prize every week to keep going.

We launched the Read-a-Thon in the last term of the year. Students could earn points for the books they read, and higher-level books were worth more points. Students submitted a weekly log of the books they finished. The points were totaled and every 10 points could be exchanged for a prize. However, just handing out the prizes seemed boring. We had to create an event! That’s where Mr. Reading Pot came in.

I had a lot of my mom’s antique furniture and bric-a-brac lying around at home. One item was this 1.5 foot high brass pot, the kind that families used to fill with grain in days long gone by. I used to stock Mr. Reading Pot with little prizes, the kind kids love: fancy pencils, scented erasers, whistles, crazy balls, small toys, whatever knick-knacks I could lay my hands on at the local department store. I’d cover the top with a small cloth, which would let a tiny hand in, but prying eyes were unable to discern the contents.

Every Friday, Mr. Reading Pot would make a grand entrance into the classroom and be seated in the middle of a large circle of squirrely kids. Mr. Reading Pot was a bad-tempered and curmudgeonly fellow. He would refuse to give up his hoard. He would shake and spin. Growl and yell. The children loved him! Each reader’s name was said aloud with the total number of prizes they could claim. They’d come up and gently request Mr. Reading Pot to be still. Then, they would carefully insert their arm into his capacious interior while he muttered threats about their fingers getting chewed up by the snakes and dinosaurs hiding inside him. The kids knew Mr. Reading Pot’s bark was way worse than his bite. Then the countdown would begin. Each winner had 10 seconds to grab a prize. Some would pick the first thing they touched. Others, like Aasiya, would stretch the time limit to the max, feeling the shape of each item, checking and double checking. When the children finally saw their prize, they let out squeals of delight or moans of disappointment, and then added to the fun by exchanging prizes with each other.

One issue we faced was how to handle students who were less familiar with English or had learning disabilities that made reading really challenging. It seemed unfair for them to see their peers walk away with prizes while they went home empty-handed. For such readers, we differentiated the point system to ensure they could win, too. This provided the scaffolding they needed to start their book reading journey. One positive result was that our dyslexic and ESL kids were reading well above the average level in other English medium schools.1

Over the years, the Read-a-Thon evolved. Bigger treats awaited the readers as they earned ice cream or pizza parties at the end of the term. Kids started saving up their points to buy a book instead of the weekly prize. Bookstores made good money off us, as children placed orders for a longed-for book. Sometimes, the prized outing was a visit to Chennai’s famous Anna Library rather than a pizza parlor.

As our school transformed into a reading school, we kicked off a number of other initiatives. We handed over the process of cataloguing to the students. They took responsibility for maintaining the library, cleaning it, restacking books, and managing the return process. We took them to the Chennai Book Fair and secondhand book exhibitions so they could buy books for the school libraries. We had used book sales at school during the monthly parent meetings so kids and parents could browse together. Secondhand books became the go-to end-of-year gifts instead of candy or toys.

We also organized one-off events to build real-life reading connections and excitement. Every year, Al Qamar participated in International Literacy Day. Another year, we invited Nilanjana Roy, a well-known Indian author, for a virtual meeting with the students. When Ms. Roy spoke about being a bookworm as a kid, it was relatable and created a real life connection where children saw that reading could actually lead to both fame and fortune (as an author). Other engaging events included the time I spontaneously bought boxes of books and made a grand classroom entry with them. Presenting students with an overflowing box of new books and seeing them ooh and aah over them was an utterly joyful moment.

My memories of the last Read-a-Thon before the school closed are bittersweet. The Read-a-Thon was in full swing and students were waiting to cash in their points for prizes. Overnight, the Indian government announced a nationwide lockdown in response to the rapidly spreading COVID-19 virus. We didn’t even have time to say goodbye, let alone enjoy one last visit from Mr. Reading Pot. The next year, the class libraries at school were bereft of little hands enthusiastically grabbing books off shelves, as teaching went online. At the end of the year, Al Qamar closed down forever.

Years later, students still contact me, reminding me they never got their prizes from Mr. Reading Pot, filling me with a deep sense of unfinished business. Other students call me up and reminisce about the Read-a-Thon. A recent call came from one of my most reluctant readers who eventually fell in love with books at Al Qamar. She is now a teacher herself, and wanted my advice on how she could initiate a reading program at her school. Another student was delighted when I sent her photographs from a PG Wodehouse exhibition at the Vanderbilt University library.

Last September, I visited the school that has emerged in place of Al Qamar. As it happens, the room I stayed in was the library, stacked with all the old books that I had personally curated over the years. Another bittersweet moment—it was as if I was spending time with children I had given up for adoption. My hands kept reaching out to stroke a book, pull it off the shelf, open and sniff the pages. The frayed labels at the back, with the catalogue information written by little hands, took me back several years as I relived the memory of bustling classrooms, animated voices, and Mr. Reading Pot.

School management and teachers who visited Al Qamar often asked how they could adopt our reading program. The question, I would ask them back, was one of priorities. Would they be willing to forgo homework or weekly tests to offer students enough time and space to read? The answer, unfortunately, was usually negative. Most schools are so hide-bound by the system that they are unable to change it, even if they know that reading offers way higher payoffs. The other issue was that most schools wanted a straightforward and easy-to-implement solution. Unfortunately, instilling the habit of reading in today’s world is an uphill battle—one that requires a sustained, multi-pronged approach. Like threads in tapestry, if just one component is missing, the whole program may fail.

There are four takeaways to consider from Al Qamar’s experience with implementing a reading program. First, building a culture of reading takes time…a long, long time. Culture is built, sustained, and passed down. Several cycles of students must go through it, and see their siblings go through it. The strong reading culture we developed at Al Qamar prevented Mr. Reading Pot’s rewards from becoming a source of purely external motivation. It also takes time to change parent and teacher beliefs about the value of reading; they need to see concrete reading outcomes in terms that they value—that is, measurable academic achievement.

The second takeaway is about prioritization. Students only have 24 hours in a day. We can overload them with books or we can overload them with homework and test preparation. It cannot be both. As school management we have to intentionally insert reading time and space—as well as discussion time—into busy school schedules. Small schools have more flexibility than larger schools in this regard.

Third is agency and choice. Kids should not only be able to choose what they read, but they should have greater participation in the entire library system. But field trips to secondhand bookstores are all too rare and most schools would balk at the idea of handing the library system over to kids to manage. Agency and choice also means we need to listen to student voice—if they don’t like book reviews, dump them. If they hate book logs, work with them to create a system where they have a different type of record of their reading, without feeling the pressure.

Fourth—and this was a work-in-progress when the school shut down—curate book collections in local languages. This would have been an important step towards affirming the students’ identities and culture.

Finally, as I would often remind myself, keep your eyes on the prize and don’t ever lose hope. Kids will read for sure, even if they take some time to turn the first page.

1. In India, English medium schools teach entirely in English.

Beck, I. L., & McKeown, M. G. (2001). Text talk: Capturing the benefits of read-aloud experiences for young children. The reading teacher, 55(1), 10–20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20205005.

Cullinan, B. E. (2000). Independent reading and school achievement. School Library Media Research, 3, 1–24.

Duursma, E., Augustyn, M., & Zuckerman, B. (2008). Reading aloud to children: The evidence. Archives of disease in childhood, 93(7), 554–557. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2006.106336.

Jouhar, M. R., & Rupley, W. H. (2021). The reading-writing connection based on independent reading and writing: A systematic review. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37(2), 136–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2020.1740632.

Mackenzie, N. (2025). The power of independent reading. Qualitative Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-09-2024-0200.

Parry, B., & Taylor, L. (2018). Readers in the round: Children’s holistic engagements with texts. Literacy, 52(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12143.

Pearson, P. D., Palincsar, A. S., Biancarosa, G., & Berman, A. (Eds.). (2020). Reaping the rewards of the Reading for Understanding Initiative. National Academy of Education.

Sanden, S. (2012). Independent reading: Perspectives and practices of highly effective teachers. The Reading Teacher, 66(3), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01120.

Sumara, D. J. (2002). Why reading literature in school still matters: Imagination, interpretation, insight (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410603449.

Tags: