Aleya and I are currently enrolled in UC San Diego’s Multiple Subject Credential/M.Ed program. We both entered graduate school and student teaching with certain ideas of what teaching should look and sound like. While working as a tutor, I realized that my perceptions about teaching were heavily influenced by my experiences as a student in teacher-centered classrooms. Therefore, I hoped to learn how to deliver content to my students in a more meaningful way. Meanwhile, Aleya was eager to build on the strategies she’d collected from teaching English abroad and working as a classroom assistant. She, too, was looking to find more effective teaching practices. This piece is a collective reflection about our student teaching experience at Baker Elementary, where our ideas about teaching were not only challenged, but completely reshaped. As we grappled with what it means to be an effective teacher, we learned to release our role as the “star of the show” and turned the spotlight over to our students. This alternative model of teaching allowed us to redefine the idea of “good teaching” that we were raised with.

While completing my minor in education, I was introduced to Teaching Children to Care by Ruth Charney. This text is a guide to proactively teaching classroom management to promote a safe, respectful, and friendly learning environment. As I read the first chapter, I was immediately taken aback by the idea that there is a time and place to teach “social curriculum.” Growing up, the rules were simply introduced by the teacher on the first day of school and we were expected to follow them. Even when I worked as an in-class tutor at different schools, behavior seemed like something students naturally came to school with and was only “dealt with” when a student’s behavior was less than ideal.

According to Charney, the first six weeks of class is the prime time to get to know students, establish a sense of community, and decide on important community agreements. Furthermore, it is a time for the students to really practice these behaviors and for teachers to make note of students’ positive behaviors (2002). Altogether, I thought these were very nice ideas but I had a hard time picturing how they would play out in a real classroom. I also doubted how effective it was to dedicate so much instruction time to “teaching classroom management.”

When I entered the graduate program, my first student teaching placement was with Melissa Han and her third grade class at Baker Elementary. Though I was not there for the first six weeks, I could tell that the class had taken the time to foster a safe and positive learning environment. I was impressed by how autonomous students were in their behavior. I remember thinking, Wow! Melissa has got it all figured out. Having the classroom management part down makes teaching so easy. However, I discovered over time that the process of teaching behavior isn’t as neat and seamless as it appears.

I distinctly remember the first time I witnessed Melissa take the time to acknowledge the class’ behavior. It had already been a rough morning and she was trying to highlight a student’s repeated addition strategy to no avail. Students were having side conversations, and even those who were engaged in the discussion were talking over each other. It got louder by the second and the tension in the room felt like a balloon about to burst. As the other teacher figure, I started to panic. What should we do?? How will we recover from this? My first instinct was to yell above everyone that they were all going to be in serious trouble. Suddenly, Melissa’s firm and clear voice broke through. Thank goodness! She asked the students to stop everything they were doing, and she made eye contact with everyone to make sure they had heard her. She then announced that the math lesson was over for the day and that we would try again tomorrow. I was intrigued and surprised that she stopped the lesson, and could only wonder what was going to happen next.

Melissa had everyone move into a circle. She was direct in naming the problem and students were to give a thumbs up if they noticed something similar. She asked everyone to look at the conversation agreement chart so we could have a collaborative conversation about why we have these rules in place. Students took time to reflect on one conversation rule they needed to remember and practice for the rest of the day, and then each student shared their goal aloud. I was totally in awe at this interaction! Rather than responding with strong-fisted authority, Melissa held the students accountable by guiding them to assess their own behavior and determining what their next steps would be.

From this experience and others since then, I’ve learned that teaching behavior isn’t a fixed process that only takes place during the first six weeks of school. The process of teaching social curriculum is continually developing and evolving throughout the school year, depending on the needs of the class at any given moment. In addition to the first six weeks, Teaching Children to Care also talks about three types of teacher talk we can use throughout the school day to teach behavior. Reinforcing language is letting students know what they are doing well so that they may keep up the good work. Reminding language is asking students to remember the expected behavior when they are starting to get off-task, or if we anticipate that they will struggle with a particular situation. Finally, redirecting language is for when the situation has gotten out of hand. With redirecting language, we ask students to stop what they are doing and redirect them to the expected behavior (Charney, 2002). The situation I shared previously is an example of how redirecting language was used to help the class remember our conversation agreements.

As much as possible, I try to be proactive about teaching social curriculum so that it doesn’t detract from teaching content. In addition to protecting instructional time, teaching behavior also scaffolds student learning. Because we have established routines for what students should be doing and how they can solve their own problems, our class is able to stay on task and be self-sufficient during independent work time. Our students also thrive when they interact as a class because they have learned communication skills such as asking for attention, taking turns speaking, and building off of each other’s ideas.

Teaching social curriculum has been both challenging and eye-opening. It’s challenging because it takes time and effort to discuss behavior with students, especially when I know there is content to be taught. It can also be frustrating because I am relinquishing my control of the situation and can’t always predict how things are going to turn out. However, teaching social curriculum has also shattered my preconceptions about teaching. I thought that teachers needed to be in control all the time and that teaching was only about the content. I’ve since discovered that engaging my students in discussion and reflection often leads to the same intended result as if I were to set all the rules, while also empowering students and meeting them where they are. Finally, by teaching content with community in mind, I’ve come to really enjoy interacting with my students because I believe they have ideas worth listening to.

I was proud of the countless teaching strategies I had already collected before I began the M.Ed. program at the University of California, San Diego. However, it was only a few weeks in when my preconceived ideas about teaching were challenged. My cohort and I were spending the morning at Baker Elementary to observe the second grade team teach their students about subtraction. One of the teachers, Sharon Fargason, worked closely with my professors at UCSD, so I knew she would be an exceptional teacher to observe. Expecting that Sharon would model best practices had me full of excitement and ready to scribble down all of her strategies. However, within the first few moments of her lesson, I felt confused by what I was watching and embarrassed to witness Sharon’s lesson fall apart so quickly. After asking just one question, all of her students started talking at the same time, unleashing a chaotic buzz that swept across the rug. The cohort and I looked at one another with great puzzlement as we were all wondering, wasn’t she supposed to be good at this? One student’s voice eventually broke through the chatter when she sat up on her knees and asked for her classmate’s attention—I felt relieved that silence had been reestablished. Yet as she spoke, I realized her idea was wrong and was shocked that Sharon wasn’t correcting her! By now, I had come to the conclusion that Sharon had lost control of her classroom and lesson and didn’t even know how to subtract two-digit numbers. I tried my hardest to hide my look of disbelief and astonishment for fear of being rude.

Once the lesson was over, I asked Sharon why none of her students raised their hands to talk. I expected her to say that they were acting out because so many student-teachers were in the room watching them. Instead, she responded, “If people don’t raise their hands to speak in the real world, why do we need to in the classroom?” (S. Fargason, personal communication, July 9, 2015). What a sensible justification, I thought. She was teaching like this on purpose! She continued to explain how she holds students accountable for their own learning and encourages autonomy, meaning they not only share their ideas, but also listen to their peers’ in order to make sense of them. Sharon described her classroom as student-centered, where the teacher’s role is to pose open-ended questions that guide students towards the learning objective through critical thinking.

By now I had realized that Sharon’s lesson was not a disaster, but, in fact, my first exposure to a technique called “Responsive Teaching.” With this approach, teachers are constantly changing their language, lessons and expectations to meet the varying needs of students throughout each and every day. This exposure taught me that becoming an effective teacher is not a destination, but a process. During this process, teachers must use their deep understanding of the content to reason how and why they do all things in the classroom. Considering this, I started to question my pre-determined ideas of teaching—why are student always expected to sit “criss-cross applesauce,” raise their hands, and wait for the teacher to give them the right answer? When I began student teaching for Sharon, I was able to see how these practices don’t work for all students in all situations. Responsive teaching became synonymous with making learning relevant and engaging for the individual student.

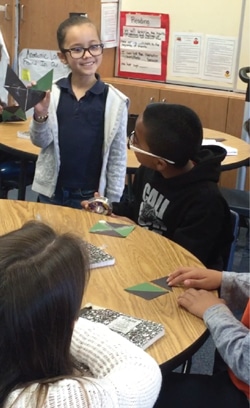

One of the first challenges I faced using this new approach to teaching was being comfortable listening more and talking less. This was difficult because although it created more space for students to share their ideas, I had a hard time welcoming ideas that were flawed instead of seeing them as learning opportunities. However, I’ve learned that unearthing these preconceptions about topics is exactly where learning needs to begin for students. I can’t guide students to conceptual understanding if I don’t understand the thinking they are bringing to the problem. During the first lesson of the geometry unit, my third graders were working with pattern blocks to describe different shapes. I was expecting them to notice how triangles have 3 sides, squares have 4 angles, a hexagon has 6 corners, and things of that nature. However, our discussion took a completely different turn when one student was convinced a corner was the same thing as a side. I could not have planned for this student’s preconception but it gave me the opportunity to turn the thinking over to the class. As they discussed their understanding of these terms, students listened and built upon one another’s ideas. In the end, we had more questions than answers, and this was okay, because it exposed me to the preconceptions students were bringing with them to the new unit. I’ve come to realize that teaching is about slowing down and going deeper with content. Doing so allows us to listen to students’ ideas and accentuate those that help other students make sense of learning—even if they are incorrect.

With this mindset, I have found that inquiry-based lessons help students make sense of what they are learning. This student-centered approach is dependent on the teacher expressing genuine curiosity in what students have to say. Rather than frantically attempting to answer their big questions, teachers show interest and encourage students to find the answers themselves. Common responses I find myself using include, “What you said is so interesting! How could we learn more about that?” Or, “I’m not sure about the answer, but that sounds like a great question to investigate.” This language not only models strategies students can use to deepen their learning but also shifts the emphasis from teacher-directed to student discovery. One morning during another geometry lesson, a student asked what shape would be created if all sides of a quadrilateral were the same length. Rather than feeling like I needed to answer the question, I turned the learning over to the students. I expressed my genuine curiosity about the student’s question and suggested he try to find an answer. All of a sudden students had their eyes squeezed shut, trying to visualize the shape, others were using their hands to make a model. Soon, voices started calling out, “A square, it would be a square!” In this instance, my role was to give students a space where they could explore their questions, instead of relying on my answers. While teacher-constructed information is an important part of teaching, it does not have to be the whole of it.

In our time as student teachers, Roxanne and I have embraced the process of taking on new approaches to teaching. Though the process is unsettling, we continue to question our teaching methods because doing so helps us think deeply about our impact on student learning. We can start by questioning why we teach a certain way. Are we doing things because that is how they’ve always been done? Are our methods rooted in evidence-based practices? Do they work best for our students’ learning styles? The journey of restructuring our beliefs is not easy, nor is it ever complete.

Charney, R. S., & Noddings, N. (2002). Teaching children to care: Classroom management for ethical and academic growth, K-8, (Revised Edition). Greenfield, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children.

Tags: