During lunch one day at High Tech High Media Arts (HTHMA), a team of two student consultants meets with a cooperating teacher to debrief a recent observation cycle. They start by giving the teacher encouraging feedback about his communication style with students and the way he seamlessly switched between slang and academic language. The conversation transitions to strategies the teacher can use to open up and connect with his students. Dialogues like these are what form the heart of the student consultant program piloted this year at HTHMA.

During the 2015-16 school year, nine HTHMA juniors served as student consultants to five teachers, all of whom were in their first year at the school. In collaboration with these nine students, Ben Sanoff, a school leadership resident, Anna Chiles, a humanities teacher, and Janie Griswold, director of new teacher development at High Tech High, formed a new student consulting program at HTHMA. This article details the origins of the project, the implementation process, and the impact of the program on the student consultants and cooperating teachers. This piece is co-written by the implementation team and two of the student consultants.

Anna Chiles is a humanities teacher at HTHMA who served as a student consultant while she was an undergraduate at Bryn Mawr College. Anna describes the genesis of the program at HTHMA.

“I’ve been thinking …” started the e-mail from Janie Griswold to me in Fall 2015. She proposed a meeting and a brainstorm about something that, frankly, I hadn’t thought about for quite some time: student consulting. The work she wanted to discuss and potentially bring to the High Tech Village was work that I was deeply engaged in during my years as an undergraduate at Bryn Mawr College. Janie’s request transported me to the rickety old classroom in the English House at Bryn Mawr, where I would sit around a table with other undergraduates doing the same kind of work that I was doing: consulting with college professors to enhance their pedagogical practices and improve classroom culture, engagement, and learning.

Over the course of four semesters, I was paired with six different faculty members. Each week, I would attend their courses for an hour, take notes feverishly, and look for evidence of engagement, relationships, and learning. I would also meet with my fellow student consultants to debrief our observations, strategize about our dilemmas, and plan how to thoughtfully, respectfully, but honestly bring our feedback and ideas to the professors who had allowed us into their classrooms.

Alison Cook-Sather developed this student consulting program, which has since spread to many institutions of higher learning where educators and administrators want to bring meaningful student voice into the classroom. Janie wanted to bring student consulting to HTH to empower student voices to support teachers new to the organization.

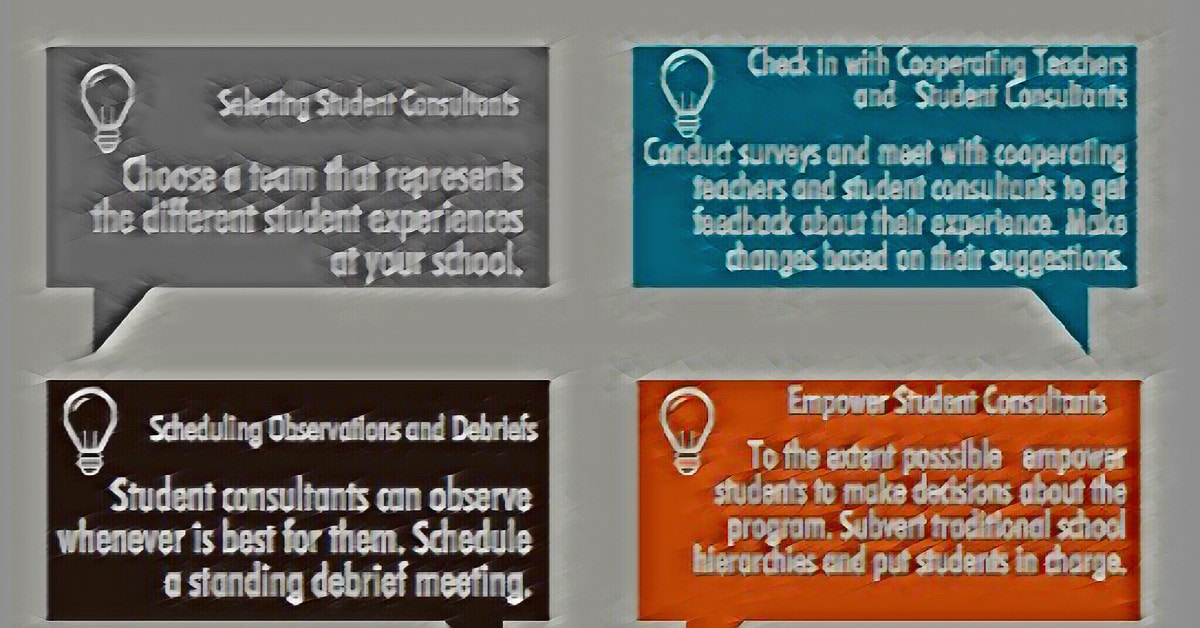

Soon, the three of us, Ben, Janie, and Anna, met to begin designing our student consulting program. When we did, we began from the model that Alison Cook-Sather, Catherine Bovill, and Peter Felten (2014) had developed at the undergraduate level. We started by identifying a group of nine HTH juniors who had experienced varying level of academic success, engagement, and positive relationships with teachers. It was important to have a range of perspectives in the student consulting pool, in order for teachers to see how different types of students might experience their classes.

We diverged from the Bryn Mawr model by adding student training, working with students for six weeks to help them develop the skills to be effective student consultants. We felt that high school students needed additional support, scaffolding, and confidence in order to disrupt traditional teacher-student hierarchies. The course consisted of watching videos of teaching, attending an instructional coaching training, observing teachers at our school site, and practicing effective debrief techniques.

In addition to these technical skills, we focused on developing a culture within our student consultant cohort of reciprocity and mutual respect between consultants and teachers. Cook-Sather et al. (2014) highlight that the foundations of an effective student consulting program are “the guiding principles—respect, reciprocity, and responsibility” (p. 169). We knew we were ready to start the program when, during the last week of training, a student consultant wrote, “It [student consulting] means that you help your teacher grow and that you build a relationship of trust and respect with each other.”

Between October and December 2016, each student consultant team conducted weekly observations and engaged in several debrief conversations with their cooperating teacher. In addition, all of the student consultants met together biweekly for forty minute sessions during High Tech High’s X-block (an elective class). During these meetings, we sought to create a safe space where student consultants could share how things were going with their cooperating teacher and pose dilemmas or questions to the group. We also organized a check-in meeting with the cooperating teachers roughly half way through the semester to determine how the program was working from their perspective and to gather feedback. Here is what we learned from students and from teachers.

The goal of this program was to foster dialogue about the student experience between student consultants and cooperating teachers. At the end of the first semester, seven of the nine student consultants completed a survey, in which all those who responded reported that their cooperating teacher listened to them always or most of the time. Six of seven respondents reported that their cooperating teacher made changes to their practice based on the consultant’s feedback.

Students’ responses also confirmed past research suggesting that when students feel listened to and have a voice in the practice of teachers, they experience a stronger sense of belonging (Toshalis and Nikkula, 2012; Cook-Sather et al., 2014). Reflecting this increased sense of confidence and agency, one student explained that for her, the highlight of participating in the program was “Becoming confident in my ability to be professional. And I also believed that I was seen as more than a student by my teacher, I was truly seen as a colleague.” This ability to disrupt traditional student-teacher hierarchies is an important outcome of the program.

Another big impact on student consultants participating in the program was increased empathy for the challenge of teaching. All seven student consultants who completed the survey responded to the open-ended question “How has your participation in the student consulting program impacted you?” by explicitly mentioning that they gained empathy for teachers. One student explained, “I now have a better understanding of the difficulty in teaching, more respect for teachers (new ones especially) and better communication and coaching skills.” Student consulting required students to put themselves in the shoes of teachers in order to understand and improve classroom dynamics.

This experience of shifting roles and imagining the teachers’ experiences helped change the way that students conceptualized school. As students gained a sense for teachers’ perspectives and struggles, they expressed more appreciation for teachers’ efforts. As one student explained, “I feel like because I have participated in this program I appreciate my education more as well as the amount of effort teachers put into their classrooms.” Echoing this same theme and expanding upon it, one student explained, “It made me a better student through perspective. Being a student consultant you spend a lot of time with your teacher and you see education through their lens. It makes you change because you realize everything you are doing is for a reason.” Students’ recognition that teaching practices are not arbitrary helped them deepen their appreciation for the value of school. This might be the reason that several student consultants also reported becoming better students. The same findings are confirmed in other research. For instance, in an executive summary of findings about student agency, the Carnegie Foundation (2015) reports, “Encouraging students to find value in what they’re learning can lead to increased engagement in the classroom, better performance on tests, and more interest in the topic you are trying to teach” (p. 10).

Julia Rosecrans, a student consultant, offers a play-by-play of the conversation that occurred in one of her debrief meetings.

We started by offering the teacher warm feedback about the classroom environment, along with their general teaching practices during the period we observed. We expressed our appreciation for the way she engaged with the students during project work time by asking questions to the students that made them think more deeply about their topics. Later in the debrief, we transitioned to some cooler feedback. We observed a need for greater student engagement during the majority of project work time, and how the classroom culture changes when she steps out of the room. This led to an inclusive dialogue about why this was happening, and we brainstormed strategies she can implement in her classroom to reach her goals as a teacher. This reflects the value of the program where we as students build a mutually respectful relationship with our teacher and generate an honest conversation about the student experience in the service of improving teaching practices at HTHMA.

Chloe Larson, another student consultant, adds that for her the program led to a greater sense of her own importance, and of mutual respect.

The student consulting program has had a huge impact on my respect for teachers and my ability to have professional conversations with them. I have gotten to see first hand what goes into being a successful teacher and all the behind-the-scenes effort that we students often miss. In one of my debrief meetings last semester with my partner teacher, he mentioned that whether or not I offered a clear solution to the dilemma he was facing, it was beneficial just to have someone with a new perspective to talk it through and pitch ideas to. I was thrilled and relieved to hear this. Being a student consultant does not mean we will always have the perfect solution to a problem a teacher is facing. However, by asking probing questions, discussing what has worked for us in the past, and offering ideas to implement, both the teacher and student can grow from the experience.

Teachers also grew from the experience. In a survey at the end of the first semester, all five cooperating teachers reported that the program was beneficial for them and that they changed their practices based on the debrief conversations with student consultants. Through such conversations, cooperating teachers reported they developed deeper relationships with students, interacted with students in a more positive way during class, communicated information about projects and assignments to students more clearly, generated better questions to stimulate student dialogue during socratic seminars, and created more collaborative learning environment for students.

For example, one cooperating teacher explained that his student consultants’ feedback helped him form more productive student groups. His student consulting team told him: “I think you would have more effective conversations if you changed your seating. You know, you have a bunch of kids who are reluctant to speak here and you have kids that embody the same mentality all sitting at the same table and they’re dominating conversations and you could break them up.” After changing the seating, he reflected, “my student consultants really helped me generate a culture in my classroom that elicited and fostered growth, communication, and discussion.” This type of specific suggestion from student consultants often helped cooperating teachers be more responsive to student needs.

In addition, the ongoing dialogue between student consultants and cooperating teachers motivated teachers to continuously reflect on and develop their teaching. One teacher described how his student consultants pushed him to improve, “Knowing that I had students that were on my side trying to make me better—it was really encouraging. They were there to listen when I voiced my frustrations and there to encourage me to continue to do things I was doing well. You know, it was a very collegial relationship, because they didn’t just pat me on the back and say, ‘Great job; see you next week.’ It was always, ‘You are doing this really well. I saw you trying to do this. Think about doing that.’ And I was constantly reflecting on what I was doing in the classroom the more we had those conversations.” Another cooperating teacher explained how: “It adds a level of accountability and authenticity that you don’t get when you have an administrator or another teacher in your classroom because students can actually envision themselves in your room and in your lesson.” The authenticity of students’ perspectives pushed him to grow more than traditional top-down feedback structures.

Just as students felt increased empathy for teachers, cooperating teachers also reported greater empathy for the student experience. According to Cook-Sather et al. (2014), this recognition of the other’s perspective is a consistent outcome of many student consulting programs. They explain, “One of the most consistent research findings in this field is that faculty and students alike expand their perspectives on one another’s and their own work” (p.110). Underscoring the extent to which the program helped teachers see their role from a student perspective, a cooperating teacher wrote, “The conversations that we had almost exclusively centered around student experience.” As teachers, we often forget about the experience that students are having in our classrooms, so refocusing attention on this critical perspective on teaching and learning can yield large dividends.

A different cooperating teacher explored the cumulative impact that paying attention to the student experience had on his practice, reflecting, “Students are the ones who are going to be in this class. They are the ones this experience is going to matter to. They’re the people we are doing this for. We’re not doing this for the administration; we’re doing this for the students.” This recognition that teaching should be oriented towards students helped teachers reconceptualize their role as one of collaboration with students. One of the teachers began to realize that, in fact, all of his students could be collaborating with him to improve the experience for both parties. He explained, “I realized that these two student consultants are helping what I’m doing with my tenth graders, and it just took a nudge for me to say I should ask my tenth graders what I need to do. And then it turned from having two student consultants to having 52. So that really impacted my teaching, because I just have much clearer pathways and means of communication with my students.” When teachers see themselves as collaborating with their students towards a common goal, it represents a powerful reframing of the teacher-student relationship.

In the coming years, we hope to help more teachers transform their relationships to students by expanding this work to other HTH schools. We are particularly excited about the possibilities of weaving the work of student consultants into the experience of teachers who are enrolled in HTH’s Teacher Intern Program. Teachers in the Intern Program teach full-time while completing coursework and collaborating with a mentor at their site in order to earn a California credential.

In other contexts, such as working with younger students, in a more traditional school setting, or with veteran teachers, this model of student consulting might have to be adapted. One alternative structure would be to have older students serve as student consultants at the elementary school level and middle school level to ensure an appropriate level of maturity and sensitivity. In traditional school settings and with veteran teachers we could envision the program being voluntary and scaling up organically based on the positive reports of teachers who choose to participate.

Providing teachers with student consultants is one way that we can emphasize the importance of student voice in shaping classroom experiences and teacher reflection. We see student consulting as mutually beneficial for participating students and teachers, helping each group transcend the divisions inherent in their roles and recognize teaching and learning as a truly collaborative process.

Carnegie Foundation (2015). Student Agency Improvement Community (SAIC): Core Concepts Description.

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: A guide for faculty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Toshalis, E., & Nakkula, M. (2012). “Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice.” Jobs for the Future, Students at the Center Series. Retrieved September 13, 2015, from https://studentsatthecenterhub.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/Motivation-Engagement-Student-Voice-Students-at-the-Center-1.pdf

For a more detailed literature review consult

http://mobilizelearning.org/?page_id=315

To learn more about our methods and the role of improvement science consult http://mobilizelearning.org/?page_id=320

Tags: