We’ve all had those days when a couple of minor things go wrong and suddenly the whole day seems a failure. I’ve spilled coffee on myself getting into the car and then gotten to school only to realize I left something important at home. Next thing I know, I’m claiming to have a “horrible day” when really just a couple of things have gone awry.

Many of our students have this experience daily. They struggle with something or make mistakes that weigh so heavily on them that these things distort their view of the whole day. These children don’t have the perspective to recognize that these moments are just small pieces of a much greater experience. They allow these negative events to color their whole day—or sometimes, alter their whole perception of themselves.

Connor is an example of one of these students. He began fifth grade at High Tech Elementary with a lack of flexibility and problem solving skills that caused him to ‘explode’ in the classroom with disruptive, inappropriate and sometimes destructive behavior. These moments were so outrageous that they captured the attention of every child in the class, and caused us all to start thinking of Connor as only a collection of these events. Connor frequently called himself “an idiot” or “stupid” and claimed to not be able to control himself—which was an understandable belief after a lifetime of experiences like these.

By October, I had witnessed many of Connor’s “explosions” followed by his belligerent defenses of “I can’t help it, I’m just an idiot.” When I sat down and carefully reviewed a typical day, I realized Connor had positively contributed to several activities when he was not having outbursts. If I could help Connor gain perspective on his behavior, he might realize that he is not defined by his explosions and see that he has the ability to do good things in school (and actually does, at times, too).

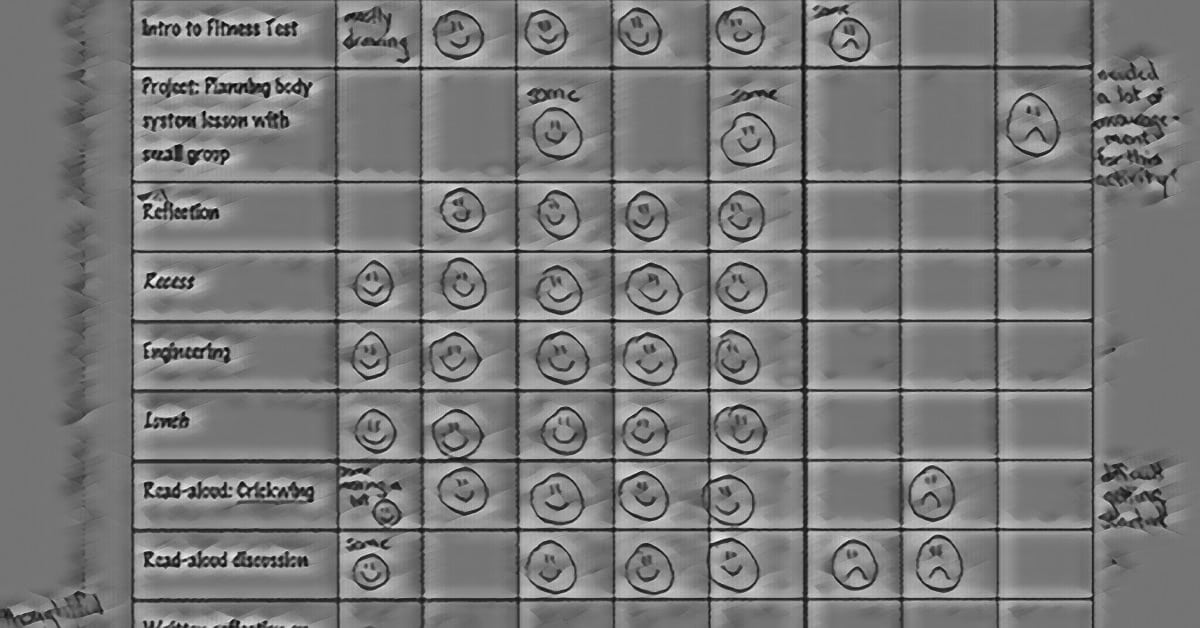

I developed a rudimentary tabulation of Connor’s day for several days to help him more objectively review his behavior (see graphic). It was basically a schedule for the events of the day—every minor activity in which we participated. As we progressed through the schedule, Connor and I reported on his behavior and participation in each task. The simple purpose was to have a clear, quantifiable representation of his day. The record was not a behavioral chart aimed at getting compliance, but rather a reflective exercise that allowed Connor to honestly view his own experiences intending to help him feel ownership of his behavior (both good and bad).

After three typical days (days in which Connor’s “explosions” were still dramatic and frequent) the records showed that there were many times during each day in which he was behaving as a contributing student in our class. This surprised Connor so greatly that he actually commented with a proud smile, “I’m not an idiot, am I?” One week of this approach helped to change Connor’s perception of himself; the reports allowed him to see that he was more than just his poor behavior. Even more noteworthy is that this shift in thinking opened up Connor to the idea that he has the ability to contribute in a positive way and it has made him willing to address his problems to help him reduce his explosions in class.

The design of this record is adaptable. For Connor, smile and frown face symbols were appropriate; they made it easy for him to quickly discern between his positive and negative actions. I also divided activities into parts so that Connor could report success during one time even if he didn’t behave well throughout the whole event.

In addition to helping Connor gain perspective on his experience, these reports, when shared with the class, helped alter Connor’s classmates’ opinions of him. His loud and frequent negative behaviors had molded their perceptions of him such that they had trouble seeing around them. The class anticipated poor behavior with every interaction with Connor. A couple of these records, shared by Connor with the class, helped revise their view of Connor and recall and appreciate moments in which Connor contributed to the class rather than took away from it.

I have used this system with other students, as well. Kristine is a high achiever who is incredibly tough on herself. On a day with several successes, Kristine only remembers her mistakes and however minor, feels discouraged by them. I created a chart for Kristine to record her personal successes and failures in a typical day. Following each activity, she gave herself a grade for her perceived experience during the activity. By the end of the day, Kristine concluded positively about her school day even though there were occasional hiccups. The overwhelming presence of ‘high grades’ helped her look past the lower times—times she normally dwelt on extensively. This experience was pivotal in helping Kristine recognize that her misperception of events was causing her distress. Since this experience, Kristine occasionally reverts back to getting greatly discouraged by events in her day; the chart she completed is a powerful visual to look back on reminding her to put things in perspective.

Helping students develop the capacity to view things objectively—to obtain honest perspectives of their experiences—is important for developing reflective students. This simple approach can help students with very different experiences better recall and candidly view their actions and behavior.

Tags: